I’ve been in my December cleaning and decluttering mood lately. At the top of my list is getting rid of the huge stack of magazines I’ve accumulated over the last few years. Today I tackled a pile of three years worth of Smithsonian magazines someone had given me a while ago. (Great browsing by the way. Interesting topics and awesome photography.) While flipping through an old December issue, I found an article entitled Untangling the History of Christmas Lights. Since our last blog was about outdoor Christmas lights, I felt duty bound to take a few minutes to sit down and read about indoor lights.

Reading about the history of Christmas lights — their evolution from lit candles gracing a tree to today’s LED miracles — sparked snippets of Christmas memories from my own childhood. I grew up in a tight community of immigrants. My grandparents, along with many of their friends and relatives, had come over from a very poor section of Eastern Europe in the late 1800s. They first settled in New York City, but later a group moved to the Midwest and established their lives here.

As many immigrants do, my grandparents worked hard to assimilate into American life while still holding onto their own familiar and beloved traditions. Over time however, their ethnic traditions blended together with newer, more modern “American” ideas and many of us in the younger generations sadly lost direct touch with our past. I’m grateful that I ran across this article; it reminded me of some important pieces of my heritage. Perhaps looking at some Christmas history will spark memories for you too. If it does, I hope that you will share those memories with us.

According to the stories my grandmother shared with me, the lighting of the tree in her childhood was the finest moment of the Christmas celebration. Just a day or two before Christmas Eve, a small evergreen tree was brought into the house to be decorated. There were a few “ornaments” — usually handmade — put on the tree, but the main focus was the lights. Christmas trees in the “old country” were ablaze (sometimes literally) with dozens of small white candles at the tips of the branches. The candles, which were carefully lit only for a few moments on Christmas Eve, represented the myriad of stars in the sky on the night that the baby Jesus was born. Those candles were meant to shine a light of hope into their otherwise very dark world.

At the age of 15, my grandmother and her sister walked across the continent of Europe to board a ship bound to the United States.They, along with many other groups of immigrants, brought the comfort of their traditions and their dreams with them to an unfamiliar and somewhat frightening new life. For my grandmother, her traditional way of “lighting” the tree on Christmas Eve was important; it spoke of her hope in a new future and it connected her to those places and people left behind.

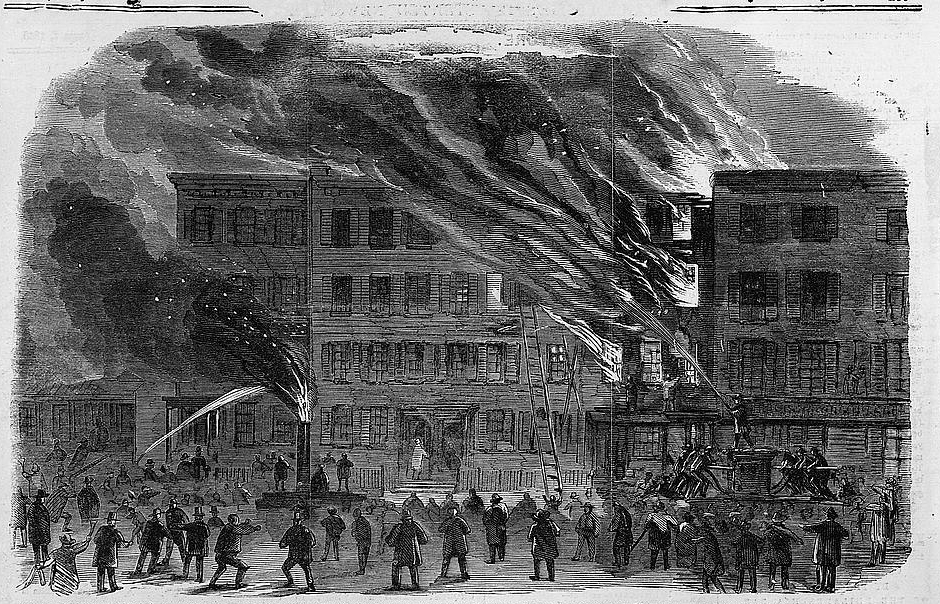

Although it was undoubtedly a beautiful sight, a tree lit by dozens of candles was also a major fire hazard. In fact, there were so many deaths and so much property loss contributed to Christmas tree fires that, beginning in 1908, insurance companies refused to cover those losses. Newspapers warned against the use of candles on trees and even adopted the tagline “A House of Merriment is better than a House of Mourning.” (I have to admit that I agree with that sentiment.)

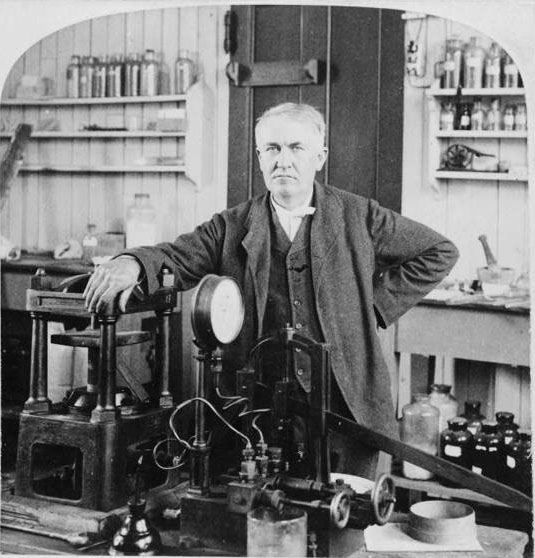

Surprisingly, electric lights suitable for use on a Christmas tree were not totally unknown in the early 1900s. In 1882, Thomas Edison and his associate Edward Johnson, displayed to a carefully selected gathering, an electrically lit, continuously rotating tree at Johnson’s New York City home. The tree, which featured eighty individually wired red, white and blue twinkling glass lights, was described by the Detroit papers (the New York paper would not cover what they termed a publicity stunt) as “a superb exhibition.”

Those few who saw it were impressed, but it wasn’t until 1895 when President Grover Cleveland placed a large, electrically lit tree in the White House that Christmas lights became a sought after decoration — at least for the wealthy. In today’s dollars, an electrically lit Christmas tree would have cost in excess of $2000.00!

By 1903, the General Electric company, seeing a sizable business opportunity, stepped into the electric Christmas light market with a less expensive version. Their pre-strung lights were considerably cheaper — they retailed for $12 a string ($80+ today), but were still far beyond the reach of the average worker whose salary was often less than $12 a week. As a result, electric Christmas lights were admired, but candles were used.

A 1917 devastating tenement fire in New York City became a turning point in the history of Christmas tree lights. The fire, begun from the candles on a Christmas tree, killed 16 people (including children), injured more and destroyed the building. It took a 15-year-old boy by the name of Albert Sadaccas to find a way to prevent similar tragedies. He suggested that his family, who already made relatively inexpensive and popular electrical decorations for sale, begin manufacturing strings of Christmas lights with their supply of bulbs. In addition to the traditional white lights, Albert suggested painting their bulbs red, green and other colors for a more festive look. Business soared for the Sadaccas and they eventually formed the multi-million dollar company NOMA, which Albert ran for many years.

In the meantime, other businesses began to produce electric Christmas lights and prices began to drop. Gradually, electric lights for the Christmas tree became more affordable for the middle class and became more common on their trees. Somewhat ironically, a number of the newly produced lights burned at higher temperatures than candles and were responsible for many tree fires.

Throughout the 20s, production of Christmas tree bulbs expanded and improved. Both bulbs and wiring became cheaper and safer. The physical appearance of the bulbs began to change and the range of colors broadened. Strings of bulbs shaped like snowmen and Santas, fruit and animals appeared. Albert Sadacca’s company, NOMA, introduced the familiar flame shaped bulbs in 1925.

Even though the 1930s saw a slowdown in both the production and purchasing of Christmas lights as the country experienced the misery of the Great Depression, public displays of lights were commonplace. Many of those displays featured entirely blue lights, reflecting the melancholy mood of the nation.

It wasn’t until the 50s when the post wartime economy soared, the housing market boomed and electricity became common in the rural communities that Americans once again felt renewed hope for the future. President Eisenhower in his 1957 remarks at the national community Christmas tree lighting ceremony, observed that the lighting of the tree “brings us together…we are not alone in a world indifferent and cold.” We are “…united in the brotherhood of Christmas.” The nation embraced his words and his sentiments and WWII’s lighting blackout disappeared in a warm glow of Christmas lights. At that moment in time,the future seemed brighter.

Through the decades, the number of candles on my grandparents’ tree decreased as the number of strings of lights increased. Finally only one candle remained. My grandmother continued to place that one old candle and holder somewhere on the tree despite its obvious shabbiness. Back then I didn’t understand why it mattered, but I think that I am beginning to finally realize what it meant to her. She saw it as hope for the future and love for the past.

Perhaps this year we will have some candles on our tree too…A ray of light in a dark night is comforting.