While cliff golden rods and rough blazing stars are vying for attention in my front garden, my third, and unexpectedly new fall favorite, quietly fills a shady corner of my backyard with tall stems covered in soft rose-purple flowers. At a first, quick glance, the plants could be snapdragons revived after the heat of summer or digitalis giving one last burst of color, but a closer look reveals an entirely different plant, rose turtlehead, or more precisely Chelone oblique. It’s a plant whose blossoms bring to mind dozens of small turtles raising their heads to see if anyone is looking for them and whose name recalls a long-ago story.

Legend has it that, during the time of the Greek gods, the woodland nymph Chelone chose not to attend the marriage festivities of Zeus and Hera and even mocked it. The royal couple was so angered by her arrogance and disrespect that they had Chelone and her household thrown into a river where she was transformed into a turtle, forced to forever carry the burden of her home upon her back as she hides from the wrath of Zeus and Hera.

Legend has it that, during the time of the Greek gods, the woodland nymph Chelone chose not to attend the marriage festivities of Zeus and Hera and even mocked it. The royal couple was so angered by her arrogance and disrespect that they had Chelone and her household thrown into a river where she was transformed into a turtle, forced to forever carry the burden of her home upon her back as she hides from the wrath of Zeus and Hera.

Named for the legend, Rose turtlehead is part of a North American native plant family originally found in the Eastern and Midwestern sections of the continent, from Newfoundland south to Georgia and Alabama and west from Virginia and Minnesota to Missouri and Arkansas. It was typically found in swamps, bogs, stream beds and moist woodlands.

There are, to date, six known species of the genus Chelone and numerous cultivars, the majority of which are hardy in zones 3 - 8. The most common species are C. glabra, a white variety found along the eastern portions of the continent, C. obliqua, our rose turtlehead native to the midwestern sections, and C. lyonil naturally found in a small area of central Appalachia. It features deep rose-purple flowers.

There are, to date, six known species of the genus Chelone and numerous cultivars, the majority of which are hardy in zones 3 - 8. The most common species are C. glabra, a white variety found along the eastern portions of the continent, C. obliqua, our rose turtlehead native to the midwestern sections, and C. lyonil naturally found in a small area of central Appalachia. It features deep rose-purple flowers.

Naturally a woodland plant, all of the various turtlehead species thrive in a somewhat specialized environment. First of all, they prefer a moderately shady environment that resembles the dappled sunlight coming through the tree canopy of a forest. They can also adapt well to both full sun and full shade, but will need some additional care to flourish. In a full sun situation, a mulch of composted leaves is advisable. In an area of heavy shade, turtlehead plants tend to become leggy and need support to keep them upright. Cutting them back in the spring will help to keep the plants bushy and will encourage flowering.

Naturally a woodland plant, all of the various turtlehead species thrive in a somewhat specialized environment. First of all, they prefer a moderately shady environment that resembles the dappled sunlight coming through the tree canopy of a forest. They can also adapt well to both full sun and full shade, but will need some additional care to flourish. In a full sun situation, a mulch of composted leaves is advisable. In an area of heavy shade, turtlehead plants tend to become leggy and need support to keep them upright. Cutting them back in the spring will help to keep the plants bushy and will encourage flowering.

Turtleheads need rich soil in order to flourish. Thin, rocky or dry soils simply won’t work for this plant. Moisture levels are also important. Keep the plant well-watered, especially during the entire first year while its root system is becoming established. Once they mature, they can tolerate brief periods of drought. Light to moderate mulching with organic matter will help to keep the soil moist and healthy.

Turtleheads need rich soil in order to flourish. Thin, rocky or dry soils simply won’t work for this plant. Moisture levels are also important. Keep the plant well-watered, especially during the entire first year while its root system is becoming established. Once they mature, they can tolerate brief periods of drought. Light to moderate mulching with organic matter will help to keep the soil moist and healthy.

As a general rule, in a moderately shady area, turtlehead plants reach a height of 2 to 4 feet, with some species growing to 5 or 6 feet. Their clumping form typically stays within a spread of about 2 to 4 feet at full maturity. Although turtleheads plants primarily spread by underground rhizomes, some varieties will self-seed in moist soils. They tend to have a relatively long life-span, under the right conditions, often living 10 or 12 years.

Chelone obliqua, the most common species here in the Midwest, add beauty to the landscape throughout the growing season. During the spring and summer, the dark green, glossy leaves and upright form add depth and structure to the garden. As fall comes and other flowers begin to fade, then turtlehead truly begins to shine. Two-lipped, snapdragon-like blossoms resembling small, open-mouthed turtles begin to form on tall, upright stems. Inside each “mouth,” there is a sparse yellow beard which is where the nectar and pollen are hidden. Once the flowers fade, pea-shaped seed pods form, each containing a handful of brown seeds.

The unique shape of the flowers makes turtlehead plants attractive to hummingbirds and long-tongued or large bees, who can open the petals to access the nectar and pollen. The foliage acts as a host plant for the endangered Baltimore checkerspot butterflies. Turtleheads are fairly deer and rabbit resistant.

The unique shape of the flowers makes turtlehead plants attractive to hummingbirds and long-tongued or large bees, who can open the petals to access the nectar and pollen. The foliage acts as a host plant for the endangered Baltimore checkerspot butterflies. Turtleheads are fairly deer and rabbit resistant.

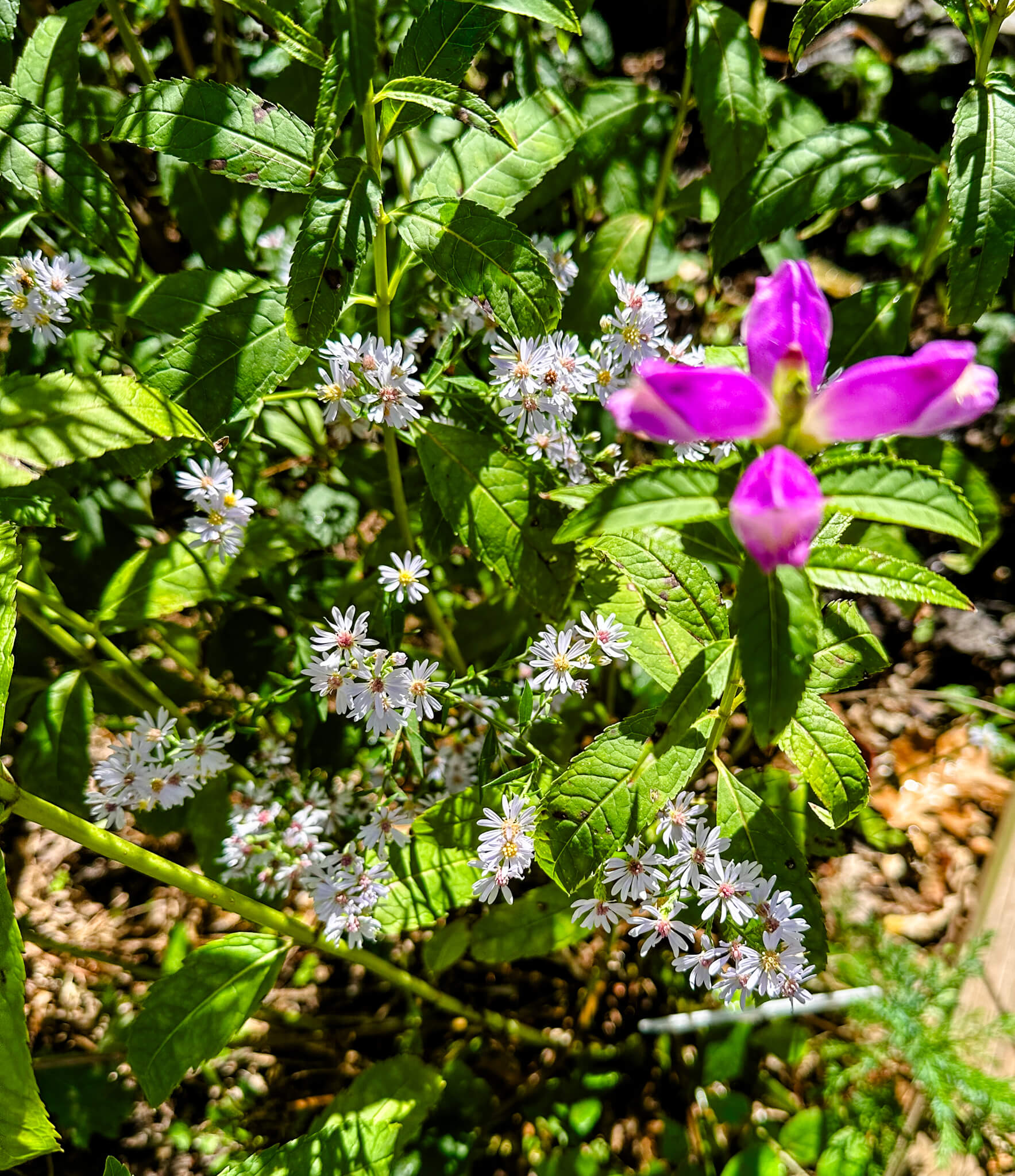

Beautiful grown in masses, Chelone also combines well with purple monkshood (Aconitum) and goldenrods (Solidago). I have it paired with masses of calico asters for an outstanding combination.

Beautiful grown in masses, Chelone also combines well with purple monkshood (Aconitum) and goldenrods (Solidago). I have it paired with masses of calico asters for an outstanding combination.

Largely unknown, this unique native plant is rapidly becoming a popular addition to rain and bog gardens, as well as to those moist, shaded spots in the landscape where other plants struggle to survive. Based on the performance in my garden, I can see why designers are adding it to their lists of their favorite plants.

Largely unknown, this unique native plant is rapidly becoming a popular addition to rain and bog gardens, as well as to those moist, shaded spots in the landscape where other plants struggle to survive. Based on the performance in my garden, I can see why designers are adding it to their lists of their favorite plants.

.jpg)